Smart bike and virtual cycling patents surround the electronics and internet connectivity that have become woven into indoor trainers and stationary bicycles over the last decade. Performance metrics like power measurement are now standard-issue for cycling enthusiasts who ride indoors (and outdoors), while virtual cycling platforms like Zwift, BKool, and others have greatly reduced the monotony – and increased the popularity – of pedaling-in-place.

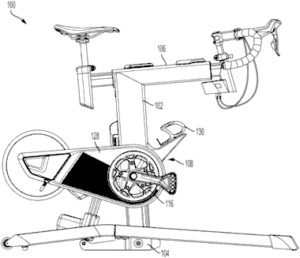

The quantum leap that stationary cycling has experienced in recent years has launched the “smart bike” – a technology-packed stationary unit that offers far more features than those of utilitarian spin-type bikes like those found in gyms. Smart bikes can also pack-in more outdoor simulation than bike-on-a-trainer setups. For example, beyond power measurement and integrated display screens, some smart bikes now include simulated slope, simulated riding surface (eg. cobblestone), and more.

Smart bikes look like an influential premium product in the indoor cycling world, with technology options that trainers cannot match. Their influence stems in-part from the delicate balance that has existed between the companies that make hardware – such as indoor trainers, powermeters, cycling computers, etc. – and software companies that provide the virtual cycling experiences. It’s generally favorable for both hardware and software companies to make systems cross-compatible, to attract the widest set of users.

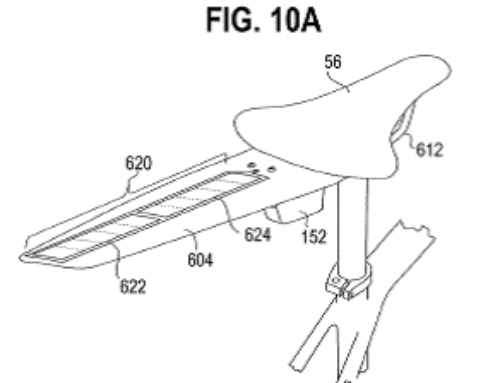

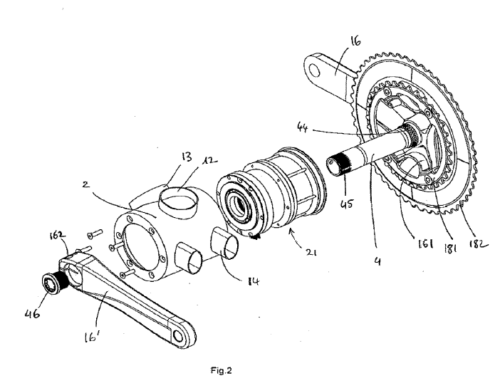

But that hardware-software balance between companies always has the potential to change, and the added ingredients of smart bikes may be a big factor in tilting the scale. A prominent company in the hardware space is Wahoo Fitness, whose KICKR smart bike ($3500 MSRP) includes features like simulated road grade that changes the angle of the bike, paired with different amounts of flywheel inertia to match the sensations of climbing or descending. The KICKR smart bike also focuses on mimicking the body position of a user’s regular bike, by integrating data from Retul, GURU, and Trek fit reports, as well as other options. Virtual shifting is also featured. Some of the technology is a blend of hardware and software.

Wahoo is staking their claim to some of this, with US patent applications (filing dates going back to Aug 2019) that appear to cover a number of aspects of the KICKR smart bike. One Wahoo related patent filing totals 49 pages, including 29 drawings and 15 pages of description — a substantial amount of material. Odds are that Wahoo’s competitors have taken notice: To avoid potential patent infringement, intellectual property counsel at companies producing similar products (or who plan to in the future) have likely combed through every word and figure of Wahoo’s patent application, while considering prior patents (“prior art”) as well.

Compared to issued patents, patent applications (“patents pending”) can mean additional concerns for companies seeking freedom to operate opinions. The claims of a patent are what define the scope of intellectual property. However, subsequent patent applications (“continuations” in patent speak) can be filed before a patent issues, with new claims that cover other aspects of the described invention. Meaning, risk assessment for patent infringement involves not just analysis of the claims of a current patent application, but also anything else that’s inventive and potentially could be claimed in the future (from what’s in a patent application’s description). Such analysis is time consuming, costly, yet the findings still inherently uncertain for a patent applicant’s competitors.

Some companies employ an intellectual property strategy of always having a chain of continuation patent applications pending, to cause competitors to spend money for legal analysis and guess what patent claims might be coming next. A company may even see if there’s material in the description section of any of their patent applications that could cover features in newly-released products from competitors, and if possible file new claims to target those specific features. How this might pertain to smart bike and virtual cycling patents remains to be seen.

In addition to Wahoo’s KICKR, other prominent smart bike offerings include Stages’ SB20 ($3150 MSRP), which includes virtual electronic shifting. Tacx has the Neo smart bike ($3200 MSRP), which includes simulated riding surfaces like cobblestones, with current availability listed for Q3 2021. Tacx was acquired by Garmin in Feb 2019. Consumer-direct brand Peloton doesn’t offer a smart bike with similar ride-simulating electronic technology, but it does include a large integrated display screen for connecting with its virtual cycling classes. The Peloton system exists in its own world, and doesn’t integrate with outside technology like power meters – unlike others, it’s a proprietary hardware and software company.

Then there’s Zwift. As a software company, integration with hardware from others has been essential for Zwift. But in Sept 2020, the company announced plans to begin designing and selling its own indoor bike, following a $450 million venture capital investment. Zwift currently partners with various bike industry companies like Trek, Saris, Elite, and others. What happens with those relationships when Zwift becomes a competitor to partners in the indoor bike space remains to be seen. So much so, that in Q2 of 2022, Zwift announced it was shelving plans for its own indoor bicycle.

But it’s easy to imagine some of the features Zwift wanted: as part of the company’s FutureWorks offerings, they currently have a virtual steering option. It works either via a phone ap (with the phone attached to the handlebars) or via the Erzo steering plate from Elite – the latter another hardware partner. Patent applications generally publish 18 months after they’re filed, and no smart bike related patents from Zwift are yet visible.

Indoor cycling continues to become more and more realistic compared to outdoor riding, which is surely a boon to both consumers and the bicycle industry. How the companies that control indoor cycling technology – including smart bike and virtual cycling patents related rights – decide to ally themselves will be key to the future of the rapidly evolving world of stationary cycling.

This article first appeared in Bicycle Retailer and Industry News