A billion dollar a year fitness company that you haven’t heard of. A massive wave of interest in indoor virtual cycling, fueled by the pandemic. An ever-increasing appetite for on-the-road power measurement. Could all of the above converge to finally bring about cleat-based bicycle powermeters? Icon Health and Fitness hopes so, aiming to succeed where entrepreneurs have failed for decades.

Building a powermeter into a cleat platform (or a shoe) is by many counts the ideal configuration for measuring wattage. Instead of being tied to a bike, the powermeter is part of the rider. Multiple bikes in the stable? Renting a bike while traveling? Hopping on a bike at your gym or in a hotel? Upgrading to a new bike or drivetrain? No need to monkey around swapping or upgrading anything — it makes owning more than one powermeter redundant. When your shoes or cleats wear out, swap the power sensor and move on. And cleats offer independent right-left power numbers for those who find that useful.

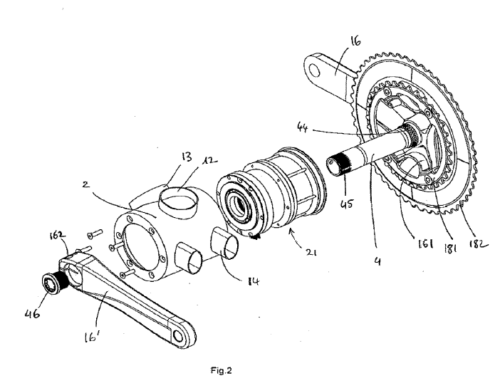

The thirst to measure a cyclist’s power is nothing new – designs for on-bike power measurement date back to the 19th century – older than the watt itself. The first viable powermeters emerged in the 1980s, when German company SRM began producing cranksets instrumented with strain gauges to measure the wattage a cyclist produced. The devices were expensive, handmade in limited quantities, and used only by professional racers and others on the bleeding edge of performance.

SRM stood alone for about 15 years, with wattage as a cycling metric surprisingly slow to catch on. But it was gradually adopted, and by the early 2000s systems from Powertap (via the hub), Ergomo (via the BB), and Polar (via the chain) were making powermeters available to a larger audience, at a lower cost. Inferred power computers, pedals, and other versions followed as interest in cycling wattage took off.

An Engineering White Whale

One of those ‘other versions’ was the highly anticipated DPMX cleat-based powermeter from Brim Bros in Ireland. It was a venture that after eight years of toil ultimately failed, causing KickStarter backers to lose over €200,000. The disappointment was big enough that CT’s James Huang did a post-mortem interview with the founder, documenting technical specifics of the downfall.

The internet is littered with the shattered remains of others who failed on a similar hunt. In 2006, two Canadian engineers formed MicroSport, and at Interbike showed a power-measuring shoe footbed. The prototype seemed to work fine on a trainer, but the venture soon evaporated. More recently, there was a power-measuring shoe from Spanish company Luck. And the RPM2 insole – first touted using pro teams, now listed on their website for running and as a “casual-use cycling powermeter”. There surely others I’ve missed – if so, please add them into the comments.

Designing a new powermeter is a seductive proposition for engineer cyclists, as I know well. In 1996 I was inspired by the still-obscure SRM, and set out with two partners to design a lower-cost system that didn’t require replacement of existing bike components. All without wireless transmission like ANT or BluetoothLE, which didn’t yet exist. Polar Electro liked the idea and licensed our patents, which used the vibrational frequency of the chain to measure power. Really. It was a solid design in principle, but the product execution was clunky, and there were a few specific combinations of gear position and cadence that could cause inaccuracies—despite years of head-banging work in signal processing. It worked fine most the of time.

What I learned from that development is that getting 95% of the way to a product that consistently gives accurate and precise power numbers is about the first half of the project. It’s the last 5% that’s so tough. Just like Brim Bros found. And like others who demo promising prototypes on trainers at trade shows. Consider Metrigear, who showed prototype powermeter pedals at Interbike 2009, delivery promised for Q1 of 2010. After a buyout from Garmin and an estimated millions of dollars in R&D, the first pedals shipped in August of 2013. And those weren’t quite problem free either.

Who’s Next in Cleat-Based Bicycle Powermeters?

Icon Health and Fitness may be the latest Captain Ahab – though no limb loss is involved. The company is a billion dollar per year global enterprise, headquartered in Utah. You likely haven’t heard of them, but they sell treadmills and other gym equipment under ProForm, FreeMotion, Nordictrack, Weider, Healthrider, and other brands. They raised $200 million in investment money in 2019, and have over 700,000 paid subscribers to their iFit platform.

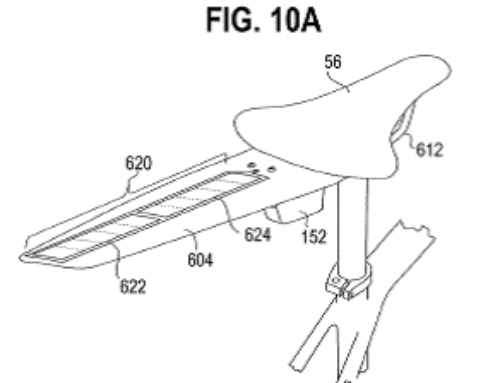

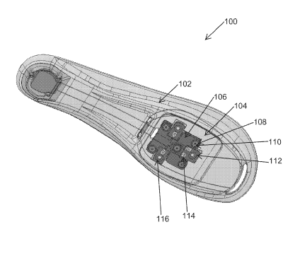

Icon has multiple patent filings on the cleat powermeters, like the recently issued US 10,786,706 “Cycling Shoe Power Sensor”, filed in July 2018. The ‘706 patent shows a sensor platform that’s sandwiched between a cleat and a shoe, with a cleat pocket built into the shoe. The platform has a variety of sensors on both its upper and lower sides, including those for force, torque, acceleration, and temperature, in any combination. The strain gauges can measure axial force, bending, and shear.

The battery is shown housed in the heal bumper – a nice clean design that eliminates having pods that clip to the shoe. But that would be a tricky as a universal retrofit, underscoring that starting with a shoe that’s designed around a powermeter cleat would make things easier. Or perhaps essential – a nail in the Brim Bros coffin was shoe sole flex. Perhaps Icon has researched that, and their platform with double sided strain gauges compensates for sole flex.

It’s impossible to know how seriously Icon is pursuing this technology, and our requests to the company for comment were not returned. But in principle, Icon has big incentives for chasing the technology. Stationary bikes often included wattage on the bike’s dashboard. Remove power instrumentation from the bike and the price of the stationary bike goes down, along with maintenance – great for gyms. Meanwhile, each gym bike has many individual users, and each one is a target for buying their own power measuring cleats. Simultaneously, cleats and shoes would let Icon sell products beyond the gym.

To date, no one has solved the cleat-based bicycle powermeters puzzle. As MetriGear found with pedals, it may require deep corporate pockets. There’s Shimano – who already makes both shoes and powermeters – but their patent filings show powermeters on cranksets and pedals, not cleats. How about SRAM, who recently acquired Time pedals, and also owns Powertap and Quarq? SRAM has ownership of at least some of the Brim Bros patents.

Cyclists ask a lot from powermeters: accurate to within a few percent, weatherproof through horrid conditions, compatible with existing bike components, configured as tiny and unobtrusive as possible, added weight under 100 grams tops or we’ll have a hissy fit. And not too expensive please. Make the battery last a long time too.

Who will be the first to successfully pack all that into a cleat-based bicycle powermeters? I’m skeptical that Icon will be the one to pull it off, at least at a level of accuracy that most CT readers would find acceptable. Maybe I’m wrong. But it’s a good bet that powermeter cleats are an idea that will continue to be chased – whether that final 5% of the problem can be cracked is the question.

This article first appeared on CyclingTips.com