Campagnolo wireless shifting was revealed by Alan Cote well before the official product introduction. Read on to see how I found out the details via published patent applications.

Campagnolo wireless shifting was revealed by Alan Cote well before the official product introduction. Read on to see how I found out the details via published patent applications.

No one from Vicenza is talking, but the rumors have been flying: is Campagnolo finally introducing wireless shifting? In 2021, Shimano went semi-wireless (no shift lever wires) with their latest generation of components, which now spans the range from Dura Ace down to 105. SRAM carries on with their fully-wireless etap system, introduced in 2015. Then there’s Classified – an entirely different approach to shifting, with a wirelessly controlled, two-speed internally gear hub. Everyone expects Campy will arrive to the wireless party too, if stylishly late.

Nothing beyond Campy’s wired EPS system has yet been spotted on bikes, but patent applications can give a sneak peek of coming technology. About two years ago, I took a deep dive into Campy’s patent filings to-date , looking at what they have disclosed and are trying to protect for wireless derailleurs and shift levers. That spanned about 10 patent applications, most as published in 2018 & 2019 – but for years after, nothing else surfaced from the company, either in patents or products.

Until now. Recently published US patent applications from Campy all are all about electronic shifting and wireless technology. In 2023, five of Campy’s US patent applications have published related to wireless shift levers, and five more for derailleurs and batteries. All indications point towards a fully wireless system, with a batteries mounted to shift levers and each derailleur. Herewith, what the legal documents tell us:

Shift levers

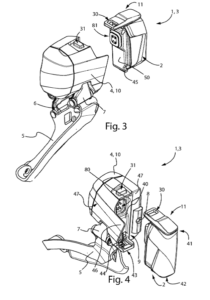

Campagnolo introduced its mechanical Ergopower brake/shift levers over 30 years ago, and they’ve remained loyal to a thumb lever on the inside of the hood for downshifts – even their decade-old EPS wired electronic shifting carried on with a thumb lever, more out of tradition than necessity. But the latest patent filings show two “control levers” on the inside of the brake lever blade.

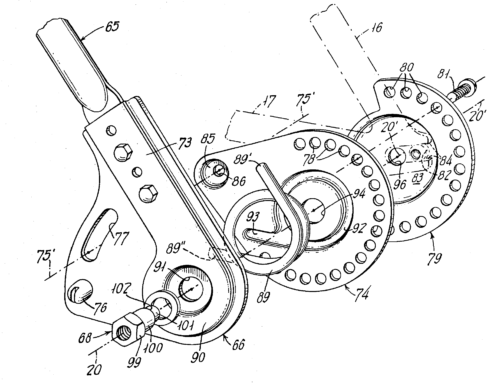

As shown in the patent drawings , there’s an upper lever (12) for upshifts, the lower (13) for downshifts. But your thumbs can still get in on the action, as two buttons (16 and 17, in yellow) on the inside of the lever body also provide shift capability. Again, upper for upshifts, lower for downshifts. Easy enough to remember in a field sprint, hopefully.

A cover (ref# 28) holds a coin-cell battery inside the lever. This provides power to a wireless communication module housed inside the lever. The wireless module includes an antenna, which has the option of being extended by a small coaxial cable inside the lever, to lessen the chances of a rider’s hand blocking the wireless signal.

The levers described appear to be strictly hydraulic for brake actuation, with details of a hydraulic tank and related workings, but no inclusion of alternate embodiments with a traditional Bowden-type cable. Which is as expected of course, as a brake cable / wireless shifting seems like an unlikely menu item.

Derailleurs

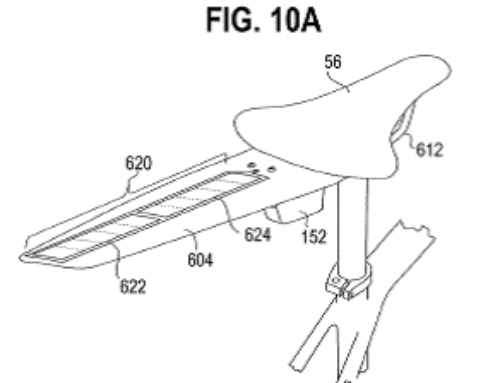

Campagnolo wireless shifting was revealed in several patent applications that describe and show front and rear derailleurs with integrated batteries. One patent filing focuses primarily on mechanical design of such removable power supplies, rather than on particulars of electronic receiving and processing components. Drawings show a front derailleur with a removable battery that mounts to the front portion of the derailleur.

In this patent filing, the same battery fits both front and rear derailleurs. There’s nothing unusual looking about the rear derailleur with a direct-mount link shown, as Campy currently uses.

The patent filings include some specifics about gears and electronics and other fiddly internals bits. “The derailleur may also include a data processing system, controlling the geared motor and any other electric/electronic components of the derailleur.” Prior patent applications covered much of that underlying technology, so this latest info suggests refinement and detail towards making a finished product work. Such as …

Notably, or perhaps not, they’ve filed patent applications for two distinctly different types of mechanisms to secure the battery in place. One style uses a hinged latch that locks the battery into place. Which may seem familiar to etap users – though it’s not necessarily an intellectual property issue. The other (Fig 20) uses a spring-loaded tab that slides, with that mechanism the primary focus of an entire patent application.

Being a patent application, Campy tries to cover all their bases by listing other components that their battery pack could power. Specifically: “… a suspension, a saddle setting adjuster, a lighting system, a satellite navigator, a training device, an anti-theft device, a cycle computer capable of providing information on the status of the bicycle, of the cyclist and/or of the route, a torque or power meter, a motor of a pedal assisted bicycle, a manual control device of another equipment, and others.”

I can imagine Campagnolo with their own power meters – they’ve partnered with SRM in the past, but have also have patent filings for crank-based torque and power sensing. With computers, there once was Ergobrain. And they show at least one ebike patent application. Dropper posts? Lights? Suspension? Hard to fathom. Likely, such inclusions are simply for patent disclosure purposes, rather than a hint of what’s in the pipeline.

And please remember my usual caveat: the drawings seen in patent applications need to support the claims of the invention, though a finished product may look quite different. But thanks to filings with the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), we have a better idea what the actual shift levers look like. Devices that use wireless transmitters require FCC certification – and a search of FCC filings yields images of a lever being tested. Like this, whose features align with what’s in the patent applications.

So is the Campagnolo wireless shifting revealed coming soon? The wireless technology has received regulatory approval in the US – which seems like a big step, showing the electronics are fully developed.

A version of this article was first published on Escapecollective.cc